Come Rain or Shine

This podcast is a collaborative product of the Southwest Climate Adaptation Science Center and New Mexico State University. We highlight stories to share the most recent advances in climate science, weather and climate adaptation, and innovative practices to support resilient landscapes and communities. We believe that sharing forward-thinking and creative climate science and adaptation solutions will strengthen our collective ability to respond to even the most challenging impacts of climate variability in one of the hottest and driest regions of the world.

Sign up for email alerts and never miss an episode: https://forms.gle/7zkjrjghEBLrGf8Z9.

Funding for the podcast comes from the U.S. Geological Survey, the Southwest Climate Adaptation Science Center, and New Mexico State University.

Come Rain or Shine

Megadrought and Aridity

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

Megadrought is a term we’ve been hearing a lot of lately, with, as we find out from one of our guests, somewhat varying definitions. The term megadrought is generally used to describe the length of a drought, and not its acute intensity. A related term, aridity, is the degree to which climate lacks effective, life-promoting moisture. Simply put, aridity is permanent, while drought is temporary. But when drought extends multiple decades, as we are currently experiencing, is it actually aridification? We interviewed two experts in drought and aridification, Dr. Connie Woodhouse and Dr. Mike Crimmins, to talk about these different terms, and discuss the changes they have been observing, and hearing about from managers and ranchers in the Southwest.

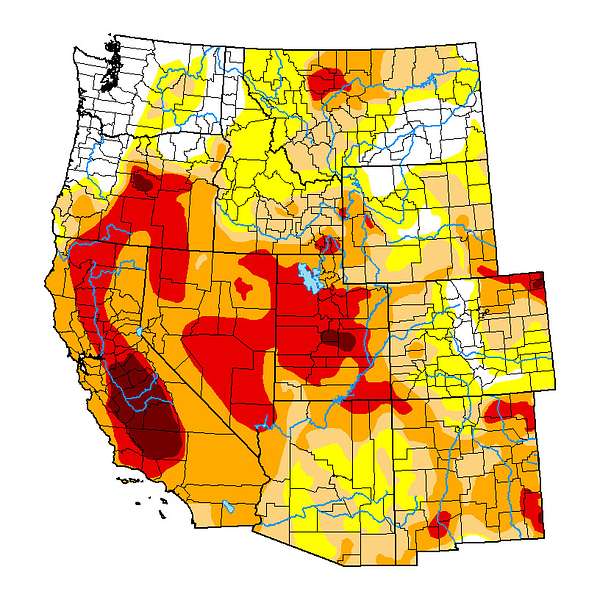

Episode Image credit: U.S. Drought Monitor - West. National Drought Mitigation Center; U.S. Department of Agriculture; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2022). United States Drought Monitor. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?West. Accessed 2022-09-06.

Links and publications mentioned during the interview:

Woodhouse, C. A., & Overpeck, J. T. (1998). 2000 years of drought variability in the central United States. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 79(12), 2693-2714.

Gangopadhyay, S., Woodhouse, C.A., McCabe, G.J., Routson, C.C. and Meko, D.M., 2022. Tree rings reveal unmatched 2nd century drought in the Colorado River Basin. Geophysical Research Letters, 49(11), p.e2022GL098781.

Climate Assessment for the Southwest website.

If you’re enjoying this podcast, please consider rating us and/or leaving us a review on Apple Podcasts, Podcast Addict, or Podchaser Thanks!

Follow us on Twitter @RainShinePod

Never miss an episode! Sign up to get an email alert whenever a new episode publishes

Have a suggestion for a future episode? Please tell us!

Come Rain or Shine affiliate links:

DOI Southwest CASC: https://www.swcasc.arizona.edu/

USDA Southwest Climate Hub: https://www.climatehubs.usda.gov/hubs/southwest

Sustainable Southwest Beef Project (NIFA Grant #2019-69012-29853): https://southwestbeef.org/

[00:00:00] Emile Elias: Welcome to Come Rain or Shine, podcast of the USDA Southwest Climate Hub,

[00:00:05] Sarah LeRoy: and the USGS Southwest Climate Adaptation Science Center, or Southwest CASC. I'm Sarah LeRoy, Science Applications and Communications Coordinator for the Southwest CASC.

[00:00:17] Emile Elias: And I'm Emile Elias, director of the Southwest Climate Hub. Here we highlight stories to share the most recent advances in climate science, weather and climate adaptation and innovative practices to support resilient landscapes and communities.

[00:00:33] Sarah LeRoy: We believe that sharing some of the most innovative, forward thinking and creative climate science and adaptation will strengthen our collective ability to respond to even the most challenging impacts of climate change in one of the hottest and driest regions of the world.

[00:00:55] The contents of this podcast are for informational purposes only, and should not be interpreted as endorsement for any of the products, technologies, or strategies discussed.

[00:01:08] Today, we're talking about drought terminology. Drought can be defined from hydrologic, agricultural, economic and ecological perspectives, and often scientists and managers add these terms to better explain what they mean by drought. Dryness or a lack of water can vary in duration and intensity leading to a variety of descriptors and scientific etymology.

[00:01:34] Recently, we have heard about flash drought, snow drought, and megadrought. Drought is generally defined as a deficiency of precipitation over an extended period of time. Usually a season or more, resulting in a water shortage. Megadrought is a term we've been hearing a lot of lately used to indicate a prolonged drought lasting two decades or more.

[00:02:00] The term megadrought is generally used to describe the length of a drought and not its acute intensity. Relatedly aridity is the degree to which climate lacks effective life promoting moisture. The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines aridification as the gradual change of a region from a wetter to a drier climate. Simply put aridity is permanent while drought is temporary, but when drought extends multiple decades, as we are currently experiencing, is it actually aridification?

[00:02:33] Today, we're speaking with two experts in drought and aridification to talk about these different terms and discuss the changes they have been observing and hearing about from managers and ranchers in the Southwest. Dr. Connie Woodhouse is a Regent's professor in the school of Geography, Development, and Environment, and affiliated with the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona.

[00:02:57] Dr. Mike Crimmins is also a professor at the University of Arizona in the Department of Environmental Science. Additionally, Dr. Crimmins is an extension specialist where he provides climate science support to resource managers across Arizona. Welcome. Connie, first question is for you. In reviewing the scientific literature, it appears that you and some colleagues may have been the first to coin this term, megadrought in a paper you published back in 1998 in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

[00:03:31] So could you define megadrought for us and contrast it with aridity and aridification?

[00:03:37] Connie Woodhouse: Yes, I can. As far as I know, the first use of the term megadrought, at least the first use in the mainstream scientific literature was in the paper that I did with Jonathan Overpeck in 1998. And in that paper, we defined megadrought as droughts that likely significantly exceeded the severity, length and spatial extent of 20th century droughts, which is pretty subjective.

[00:04:01] Subsequent studies have used this term, but they've adopted their own criteria or used somebody else's criteria. And these have included specific duration intensity thresholds. So as you can see, the definition varies and it can get a little bit messy. So a couple of examples, there was one paper that used running ten year means below a certain threshold.

[00:04:22] And the years encompassed by those running means. And another case, the period evaluated was 19 year averages, and the 19 year periods below a threshold. So here it was more the intensity of those 19 year periods rather than the duration, although that was, you know, 19 years is about two decades.

[00:04:42] In another study, 35 year periods are used. So. The megadrought events are then defined as being the worst in intensity, worse than anything in the 20th century. So the 20th century is kind of that baseline. And then there's usually a number of candidates and they're ranked and identified that way. So these are cases when the paleo data are annually resolved.

[00:05:03] So you can say a 19 year period, or 10 year period, and these data are from tree rings. There are cases when we don't have annually resolved data that we're using in these megadrought definitions, things like lake sediments. And in this case, megadrought definition is more of an assessment of the agreement among large number of different kinds of paleo records documenting prolonged drought at the same time, across a large region.

[00:05:26] And that was like our 1998 study that used tree rings and lake sediments and different kinds of proxies like that. But getting back to the definition of megadrought, as you can see, it's not very straightforward, but very loosely with regard to drought duration and intensity and extent. Here's what we can say:

[00:05:46] There's general agreement that megadrought duration is a multi decadal or longer period with hydroclimatic conditions below a threshold. And again, it's usually assessed in a smoothed record. We're not so much looking at individual years, but, you know, periods of time averaged over a decade or so either intentionally or because we've got, you know, paleo records that don't have annual resolution.

[00:06:10] So that's the duration. We do talk about intensity and severity, which is measured in a variety of ways, but again, typically this is assessed as more severe than the conditions in the 20th century or sometimes the instrumental period. And this has been applied to both the paleo droughts. So droughts before instrumental records and 21st century droughts.

[00:06:32] So again, looking at that 20th century period, as sort of the baseline for comparison and particularly the 1930s and 1950s droughts. So in terms of intensity and severity, once we have the, you know, the candidates identified, they're often ranked and often we see studies that say, this is the worst megadrought in 800 years.

[00:06:54] With regard to spatial extent of megadrought. This has not typically been a part of the definition. megadrought may be defined in terms of the context of a region like the southwestern United States or the western United States. But overall, these are generally widespread events. So megadroughts in contrast to aridity:

[00:07:15] to make things more confusing, the term aridity has been applied to describe megadrought conditions. And this is because these megadroughts are persistent and you have arid conditions, you know, dry conditions that are persisting that look like aridity describing a long term condition. But when used in this way, of course, it's not considered permanent aridity.

[00:07:35] It's, you know, a characteristic of that event. And then finally aridification, how does that relate to megadroughts? As you said, aridification is the process of becoming dry or arid and since megadroughts have been considered events and the process of aridification is considered more of a regime change,

[00:07:54] this really hasn't been applied to megadroughts. So, although it's an interest, an interesting question might be when does a very long drought become part of the process of aridification? I think we're gonna address that later on in the segment, but it's kind of intriguing to kind of figure out, you know, where one moves into the other.

[00:08:13] Sarah LeRoy: Thanks, Connie. And yeah, we are gonna talk about that in just a little bit. Mike, I want to give you the opportunity to add anything to those definitions or descriptions.

[00:08:21] Mike Crimmins: No, I mean, Connie's gotta spot on. I get confused now, too, about what we're talking about when we're talking about it. I do think that a lot of the work that we need to do, and I'm happy to talk about this on the podcast is to try to disentangle them and try to understand when we're talking with people,

[00:08:37] what actually are we talking about? Are we talking about drought? And then when we're talking about drought, what do we mean by megadrought? And then the aridity aspect is really, it's a longer term challenge. Conceptually to get people to have to get their heads around it because it's slow change just by its very nature.

[00:08:54] It's very, very slow, tracks with temperature. And so I think that's the real challenge in getting people to kind of recognize it.

[00:09:01] Sarah LeRoy: Well, that's a perfect segue into my next question, because I wanted to ask you, Mike, since you are an expert in working with partners and especially ranchers. So I wonder when you're talking to these groups of people and, you know, if you often use these terms, or if you hear from them, you know, using the terms, drought, megadrought, aridification, do they understand the difference between the terms? Have they heard them before?

[00:09:26] Mike Crimmins: Yeah. So when I started this job, gosh, I think it was 17 years ago. It was, so it was right after the 2002 drought and I'd gone to grad school at U of A and kind of, and I lived here, lived through that drought. And I studied fire and climate and so I didn't really have any drought expertise.

[00:09:43] And so this job dropped me into that period. And so my whole job has been, I guess, a megadrought, right? So it's been the entire duration of this last 20 year drought. And in working with ranchers and farmers, anyone who's worked down here, multi-generationally, they're used to drought, right?

[00:10:04] I mean, the Southwest has, right outta the tree ring research Connie's work episodic longer term droughts. And we have all these different time scales of droughts though that people are experiencing and managing through. And that was I think, and still continues to be the most interesting thing and aspect about working on drought down here in the Southwest is that the time scales of drought are really really important in the sense of when you're talking with somebody, you're not always talking about the same timescale. And so, and I think this has been really interesting in watching this sort of megadrought discussion because as Connie kind of talked about, the spatial extent and the duration, intensity drought has really been wrapped up in Lake Mead and Lake Powell.

[00:10:46] And it's been broader, larger basin wide multidecadal precipitation deficits. And so, you've got all these people living and working in these basins who may or may not be attached to the river or you know, kind of dealing with water issues. And if you aren't, you're probably not paying attention to it in the same way.

[00:11:05] You're not seeing a 20 year drought. Ranchers who work in the Southwest are, they're basically they're agroecosystems, right. In the sense that they're running livestock on summer rain fed grasses. Right? So when we talk about drought to ranchers we're really talking about, did that monsoon rain or not?

[00:11:27] Right. So you know, that a drought discussion with a group of ranchers is we're really talking about summer precipitation and then secondarily water resources that their livestock are using are sometimes tied to the longer term drought. Sometimes they're not, right. A lot of the work we do as far as drought management and adaptation plans for ranchers is actually getting water sources that are not tied to climate. And so that we take that part of the equation then is it just, does it rain or not on that, you know, summer pasture. So that has always been interesting to me because you know, the news has talked about megadrought and it's used it in some interesting ways.

[00:12:04] Like, you know, there was a deep episodic kind of year drought, 2017, 2018. And it really caught, that was a winter drought and it was fall, winter really got a lot of attention. It was definitely part of the 20 year drought, different set of impacts there. The failure of the monsoon in 2020 was called megadrought.

[00:12:21] So just the summer failing was then megadrought. And you're like, no, that's not what we're talking about here. And so it's kind of wandered its way through the media sphere. And I do think people are confused now, right? And I think the way Connie laid it out is the way I've always thought about it. And that goes right back to sort of original papers.

[00:12:39] We're talking about extent, duration and intensity. That extent, duration and intensity usually then shows up in water resources at longer timescales. And trees too. But then if you get down to the sort of shorter term variability it's, you know, can be in and outta drought several times at shorter time scales in a five year period.

[00:12:59] Sarah LeRoy: Thanks Mike Connie. So the paper that we were discussing earlier in 1998, describes different scientific methods to explore the past, to understand how more recent droughts fit within the historic record, which you mentioned, such as lake and other sediments and archeological records. And so one of those methods is your area of research, which you mentioned dendochronology or tree ring analysis.

[00:13:24] And in fact, a few months ago, we spoke with a scientist using tree rings to understand drought impacts to forests on the Navajo Nation. And so I'm wondering if you could talk about your work to understand the recent megadroughts and how those megadroughts fit within past centuries.

[00:13:41] Connie Woodhouse: I use tree rings as proxies for past climate.

[00:13:44] And one focus in my work has been to investigate past droughts. In particular, my colleagues and I have used tree rings to reconstruct stream flow. That's been, you know, one of the main areas that I've looked at and looking at major rivers in the Western United States, including the Colorado river basin, which has been a real focus.

[00:14:02] We haven't really targeted megadroughts per se. And part of that is because of the ambiguity of how this term is defined. But we have looked at periods of below average stream flow in these long tree-ring based reconstructions to get a better idea of the range of hydrologic variability in extremes that have occurred over the past centuries to several millennium.

[00:14:23] So, I just wanna mention our most recent paper, which came out a few months ago, another Colorado River reconstruction. We were able to extend it back 2000 years. So that's the longest record of Colorado river flow that has been generated. So in some cases like, “so what?” another reconstruction of the Colorado River, but in doing so we discovered a century of amazingly persistent intervals of below average stream flow.

[00:14:51] And this occurred during the second century. So during the century, there are four periods of consecutive below average flow years lasting 10, 13, and even 24 years. This is something different than we've seen in any other reconstruction. And certainly doesn't even come close to what we're seeing in the current drought.

[00:15:13] So this reconstruction definitely has no uncertainties. We don't have a lot of data back there 2000 years ago. But it does suggest prolonged period of aridity, and I'm gonna use that word aridity, that was far longer than even the megadroughts that have been identified in other papers that occurred notably in the medieval period.

[00:15:31] So that was between about 800 and 1300. And this is something different. We didn't use the term megadrought. But these are in terms of persistent low flows, these are quite notable anomalies. They occur during a time that was not as warm as today. So that's one thing to keep in mind.

[00:15:49] Emile Elias: So Connie, that's really interesting that you chose not to use the term megadrought.

[00:15:54] And was it partially because of the ambiguity surrounding that term?

[00:15:58] Connie Woodhouse: Yeah, it just, you know, if you've got someone saying we're in a megadrought right now, which certainly there have been a lot of papers saying that, it was really be hard to sort of say, oh, well, here's another megadrought when it really we're talking about a very very long period of consecutive below average flow years that were due to lack of precipitation. Versus what we're seeing now, which is low flows that are driven by, a lot by temperature. And so they’re different, it's a different beast.

[00:16:29] It's, one of my colleagues, Dave Stahle wrote a perspective piece for Science on a recent paper that came out and he called it, I think An Anthropocene Megadrought, something to distinguish the current drought from these droughts that we see in the paleo records in the past.

[00:16:48] Emile Elias: Yeah. Thank you. Thanks for that clarification. That's really helpful as we're thinking about these terms. So Mike, this next question is for you, you lead a project called MyRainge, and that makes it possible for ranchers to monitor precipitation in remote areas of their rangelands, and then link that precipitation with vegetation growth.

[00:17:11] And so I'm hoping you can tell us a little bit about what you're hearing from the ranchers and your partners about what's happening on the ground. And especially are they reporting any short or longer term changes related to water scarcity? And you touched on this a little bit around the summer monsoon and the importance there, but I'm just curious about what you're hearing from people that you work with.

[00:17:36] Mike Crimmins: Yeah, thanks, Emile. So that particular project was a way of connecting with ranchers and land managers on something very tangible and specific data wise that they thought would be helpful to them. And so that's been a really fun project and I think I've learned way more about how they use information through that project. than I have any other one, and my hope is that it actually has been helpful. The joke at the beginning of the project was that the rain gauges didn't come with rain. So, and we started that in 2015 and we've had a couple of sort of bumpy summers, including that 2020 that I talked about. But the last two summers, in Arizona largely, have been pretty good.

[00:18:20] And I know New Mexico has had a little bit of a different experience, especially last summer. And I think you're doing a little bit better this summer, but again, working with ranchers who work in the Southwest, who are working on these summer dominated rangelands, meaning summer precipitation dominated, it rains, things can turn around quite quickly. You know, I've talked to colleagues who do more on the rangeland monitoring side, and there certainly have been changes as far as, you know, species composition and you know, there's in some areas there's, you know, the worry about woody encroachment and those kinds of longer term changes.

[00:18:57] And invasive species, you know, kind of always there. And those are not purely climate driven. They're, you know, a lot of those are sort of the really complex interaction, but again, you know, getting the rain at the right time is really beneficial. And so, you know, a lot of the conversations I have are “it rained over there and it didn't rain here.”

[00:19:18] Right. And when they say it didn't rain here it's they wanted it to rain there. Right. And so I was at a meeting a couple weeks ago and I was getting reports from around the state and you know, about half the people are happy and half aren't and that's kind of on average. So I do think this is the challenge though, when we're talking about drought versus aridification, is that, and again, you've look at the climate projections from down here.

[00:19:40] There's not real clear trajectory of the monsoon. We're just not sure. You know, it's not like we expect it to sort of shut down in the next 10 years and then that's it. Looks noisy. It looks like it'll be noisy as it has been. You know, we expect heavier rain with more water vapor in the atmosphere, but that aridfication is that as it gets warmer, the way water moves through the landscape is gonna be different.

[00:20:04] Right. And when you have a really good wet summer and it's warmer, it's not quite as wet as you thought. And I think that we're not totally sure how that manifests itself in these systems. Will it be really noticeable really quick, or will it not be noticeable for decades? I'm not totally sure. Especially when it comes with summer rainfall.

[00:20:26] Right. And so these rain gauges, I think, will be really helpful kind of on a season by season basis. But again, we don't expect to see real strong trends and even in precipitation down here. It again the aridity part, the increasing evapotranspiration, increasing stress on the vegetation on the landscape is gonna play out over a long period of time.

[00:20:44] It's just harder to pay attention to. And I think that's where our research needs to get pointed and the way that we interact with our stakeholders needs to get pointed as well.

[00:20:54] Emile Elias: That really sets us up well for our next question, Mike. So thanks for that. We at the Southwest Climate Hub have a team meeting every week and sometimes we use a chat waterfall, so we'll put a question into the chat, everyone will answer it, but they won't hit enter until the same time. And we told the team that we'd be speaking with you and the most common question in our chat waterfall really points to what you were just talking about, Mike.

[00:21:22] And that question is at what point does a megadrought become aridification or another way to phrase that is when do we need to widely reclassify the system based on that? So, Connie, we'll start with you on that question.

[00:21:44] Connie Woodhouse: That's an interesting question. And I think I hinted at that a few minutes ago, when does a very long drought become part of the process of aridification and, you know, I think we're seeing that now. Kind of opening our eyes to that possibility.

[00:22:00] However we'll always have droughts and some of them will be quite persistent. We've definitely seen evidence of this in the paleoclimatic data. And conversely, and we haven't talked about this - we'll have periods that aren't classified as drought. However you define that. You know, the climate is gonna continue to vary even as we shift to a more arid climate as is projected.

[00:22:21] And as we're seeing occurring in this region. So droughts will be exacerbated by warming temperatures. And now we're seeing that happening and the wetter periods are gonna be less effective at replenishing moisture deficits. And I think it's maybe more important to recognize this than to determine when a megadrought becomes aridification, which gets really complicated because again, it's how you define megadrought.

[00:22:45] And is that a term that resonates with everybody? As Mike mentioned, we have this thing, the monsoon, which seems to be doing its own thing. How does that play into megadrought? So interesting question. I'm sure Mike can comment on this as well.

[00:23:02] Mike Crimmins: Yeah, no, Connie, I completely agree. And this is what I think it's so interesting in working in the Southwest where we have these two seasons of precipitation.

[00:23:10] Right. And we think about the Colorado River, the upper basin, it's winter dominated, right? So it's a little bit cleaner signal, you know, less of that ENSO, El Nino Southern Oscillation Connection, creates its own kind of quandaries as far as trying to think about how things will change in the future.

[00:23:25] But yeah, down here in the Southwest sort of Arizona, New Mexico, what if summers get wetter? Which some projections, not all, some suggest. What does that water do in the system? Is it enough to offset the warming? If we start to see decrease in precipitation, a lot of these systems have evolved and adapted to, you know, getting winter versus summer.

[00:23:47] The system will change. Even if that water balance is sort of satisfied in different ways, it still will mean change. And it's certainly our water resources are not tuned up to large changes if we have shifts in seasonality as well. So that's something that we got to kind of get our head around as well.

[00:24:03] And Connie, to your point too, I have to give a talk tomorrow on sort of climate change in the basins. And I have your GRL paper up here, and I'm always intrigued to look at the variability over decades and recognize that we will have a shift back towards a string of wet winters. We just don't know when, right?

[00:24:25] I mean, it could be, it probably won't be this winter, but I don't know, a couple years from now, what if we have a run of five and we, it gets really wet here, right? I mean, at that point, you, if you're talking about the term drought. Droughts end, you know, if we're seeing precipitation amounts that reverse the way we do drought monitoring, we start to see rebounds in water resources.

[00:24:45] We will have to call the megadrought off at that point. It will be over because droughts have to end. But it'll be in a warmer climate, and that's where the real work is, is that I think the real work is gonna be in the wetter periods to really understand if they're effectively the same as they have been in the past or not. Everything that we know as far as the hydrology and the thermodynamics and all the physics is that it won't be, but how it will be different is not super clear to me.

[00:25:14] Connie Woodhouse: And I think the other thing that's kind of related to that is the fact that the monsoon and the cool season. Those precipitation regimes aren't independent in terms of their impacts either. So I've been doing work trying to determine, you know, what the impact of monsoon climate is on stream flow, which is largely dominated by the cool season by snow.

[00:25:35] But it turns out that summer temperatures are pretty important for stream flow, annual stream flow. So even if we don't, even if the monsoon is wet and the winter is wet, if we have warmer summers. That's gonna have some bearing on the runoff that we get. So these things are connected and I think it behooves us to really pay attention to these changes in climate, changes in aridity, even without megadroughts.

[00:26:01] Sarah LeRoy: Well, following up on that question, you know, when a megadrought becomes aridification and Connie, you may be alluded to, there might be some areas, or we might be seeing that happening already. And so I just wanna ask you, do you think that some areas have already undergone aridification, you know, meaning that they have permanently changed and maybe we won't really be able to know this, like Mike said until we get those more wet years and can kind of compare those wet years to wet years in the past. But maybe Mike we'll start with you on this question and maybe, you know, what you're seeing on the ground. Are there areas undergoing aridification that we see now?

[00:26:40] Mike Crimmins: Yeah. I think it's a really good question and it's almost impossible to answer.

[00:26:45] It's one of those things that if we're talking about like some kind of change on the landscape, you know, there's never really pure attribution to one thing anyways, and it's always some complex interaction. Right. And it's really the way climate change actually kind of cascades through all of our lives.

[00:27:02] Right. Is that. It is part of everything and it's not the sole cause of anything. I mean, it, it exacerbates and enhances and in some cases suppresses, you know, different kinds of impacts that we would normally see on the landscape. Right. So I think that's really challenging, but I was looking at, so for some new projects we're spinning up, with the Climate Assessment Southwest, I'm looking at some papers just on, you know, some measurements of things related to aridity.

[00:27:30] And so one of the things that is completely intertwined with this is the measurement of evapotranspiration. And so in, in climatology, we talk about potential evapotranspiration, and we've got equations that if we take meteorological measurements like solar radiation, wind, relative humidity and temperature, the interaction of all of those drive the flux of water from the landscape.

[00:27:55] Right. And so talking about climate change and aridification increasing temperatures are part of this equation and can drive increasing levels of aridity because aridity by definition is that you don't have enough precip coming into a system to balance out what's leaving through evapotranspiration.

[00:28:13] Right. And so it's, there's aridity indices that are just the ratio of those two measurements. So a really cool paper, some colleagues out of Desert Research Institute have already shown that in the Southwest, potential evapotranspiration rates are on a trend and they're, you know, they're several inches higher than they were two or three decades ago.

[00:28:33] Right. So even if we're not seeing the direct manifestation of that on the landscape, the metrics are already showing that the region is drying out. Right. And so, and this is kind of on, and again, this is the real challenge too, right? These are on annual time scales. You add them up. But we don't live on annual time scales.

[00:28:52] We interact with weather on day to day basis and I'm, you know, it's, storms are building on the mountain right now. The humidity is extr... you know, it's soupy and Tucson and it's gonna rain and I've had several inches of rain, right? So aridity is gonna play itself out over longer periods of time, thinking about annual to many years, and it's gonna be these real subtle changes.

[00:29:14] And so looking for those changes in the landscape is gonna be challenging.

[00:29:18] Sarah LeRoy: Connie, do you have anything to add to that?

[00:29:20] Connie Woodhouse: Not really except that I think Mike mentioned this at the beginning, is that kind of tangled up with this changes in landscapes due to aridification is land use. And I mean, we just have one historical great historical example of that.

[00:29:33] It wasn't permanent, but the 1930s Dust Bowl drought was exacerbated by the land use at the time. Really made much worse because of the feedbacks related to the agricultural practices. And luckily, you know, that was reversed due to better agricultural practices due to groundwater pumping.

[00:29:52] But the land use is really closely tied to this aridification process.

[00:29:57] Emile Elias: And that leads in you've already really started to answer this question, but as we were preparing for this, I was talking to some scientists at the Jornada Experimental Range, and they were discussing an open question that scientists from NOAA and USDA are discussing.

[00:30:13] That is how land degradation exacerbates meteorological drought. This of course can lead to plant stress without any change in precipitation amount. And so a colleague recently noted that there are feedbacks between aridification and land degradation. And it's an open question to what extent we can intervene in those feedbacks.

[00:30:36] So I know this topic, and you've already started down this road, but this topic or conundrum is interdisciplinary and nearly impossible to answer as Mike mentioned. And at the same time, I'm curious about your thoughts on these ties between land health and drought or aridification and wherever we fall on that scale and then management.

[00:30:59] So do either of you have anything you'd like to add? And Mike, we'll go ahead and start with you based on the research that's starting through CLIMAS.

[00:31:09] Mike Crimmins: Yeah. And again I think it's such an interesting question and I think Connie's example of sort of the thirties, which were really, I think, instructive. I think there were several instances of, like the development of the Soil Conservation Service in the early past century. And, you know, Extension was actually right...that was one of our big jobs in the early last century was just helping with land soil stabilization and soil management and those kinds of things. So, yeah. So I do think that management and our sort of the way that we interact with the landscape is, it's primary and that droughts occur and how we respond to these droughts,

[00:31:50] and the interventions that we can do, or the management actions that we can do are important. And then I think aridity is like, third, right? It's that, there's this change going on at the same time. And I think that at that point, you're probably start to see, and we've seen this, you know, I think across the west, in this last 20 years, is that some of the things that we used to do just aren't quite working anymore.

[00:32:13] So I think that's where aridity starts to show up. Right. It's that the droughts have a character to them that is different and more intense, even given that the precip anomalies, maybe aren't as, you know, remarkable, that you're starting to see impacts emerge. Right. And I think that, you know, drought impact monitoring and kind of rallying around sort of studying the landscapes in these is really really helpful.

[00:32:40] So I, I think it goes that direction, and, you know once you have an impact, then this is what we saw in the thirties. Right. And we continue to see here is like, once you lose a landscape's vegetation, you have really trouble stabilizing soil and you can have erosion and those kinds of things. Right. So it feels to me it's kind of that direction, especially in the water limited systems of the Southwest, is that it kind of goes in that direction rather than the other way around.

[00:33:05] I think once a landscape does kind of cross over. We see, this is the work that Jornada's done for a long time is thinking of these state and transition models is like, what's the energy and what's the intervention to shove it back in those other directions. I don't know. And I think it's hard. And I think that this is where our research has gotta get more clever on trying to understand where those states are. And if you can move them in the other direction.

[00:33:31] Sarah LeRoy: So I'd like to shift gears just slightly and talk a little bit about communicating about these different terms. So a few months ago at an Adaptive Silviculture for Climate Change workshop held near Gunnison, Colorado. They identified resilience to aridification as a goal.

[00:33:48] And so I'm curious what you think are some of the best ways to communicate about the differences that we've talked about today, between aridification and megadrought. When, you know, when we're communicating with land managers. And so, Mike, I think we'll start with you on this question.

[00:34:04] Mike Crimmins: Sure. Okay. I think that making a distinction between, I think it's just what you said is making a distinction between aridification and drought. Droughts by definition have beginnings and ends.

[00:34:15] Right. And they're I, and I think maybe going back to what I talked about earlier too, is that I think we need to be really clear when we're talking with a specific audience. Making sure that you're on the same page about what do you mean by drought, right? And that you can get very specific about, it doesn't rain when? or is it snow? Or is it both? Is it some kind of excursion from average precipitation that is a season, many seasons? Those kind, you know, like getting very specific, I think helps, because then you can talk about it in terms of a drought beginning and a drought ending. Right.

[00:34:50] You can look for the signs. And then move towards this discussion about aridification, which is okay. So when a drought begins and a drought ends after the drought ends, what are your expectations? Right. Are your expectations being met? I mean, if it is indeed ending from some, you know, drought index, are you seeing whatever you'd expect to see as far as, you know, a management objective or an intervention, those kinds of things. You know, I think this is, this has been really interesting in the wildfire community.

[00:35:24] Talked a little bit about this spring and you saw this in the postmortem report from the fires in New Mexico, is that there's kind of a growing understanding in the wildfire community, that the metrics and sort of the prescriptions and the way that they use the information hasn't accounted for the warming temperatures and, you know, largely it would play out as aridification. And so that there needs to be a rethinking of how these indices track longer term accumulation of fire danger. And if they really make sense as the temperature goes up.

[00:35:57] So to me, I think that these kinds of making that distinction between a drought is a drought and aridity is a longer term systemic change is really important.

[00:36:06] Sarah LeRoy: Thanks, Mike Connie, is, would you like to build on that?

[00:36:08] Connie Woodhouse: Yeah, just a little bit. I mean, just to reiterate, I think what Mike is saying, I think it's really important to convey the idea that warming temperatures are conditioning our climate towards increasing aridities. It's happening in all seasons with all types of precipitation. So rainfall, snow, the same amount of rain and snow are gonna yield less effective moisture because more of that, moisture's gonna be lost to evapotranspiration.

[00:36:32] This is gonna happen during periods of drought and it's gonna happen during periods that are near normal even wet. I mean a really graphic example of this is in the snow pack in the upper Colorado River basin. It's been near average for a couple of years, like 2020 and 2017 was near average or above average at peak, you know, snow like April 1st. But the runoff was below average.

[00:36:57] So what was with that? Well, that's the effect of warming temperatures and it's become now this sort of awakening and realization that just because we've got average snow pack doesn't mean we're gonna have average runoff. In fact, we can almost guarantee that it's gonna be less than average. So that's a real obvious impact of the warming temperatures.

[00:37:18] Even during times when we're not really saying we're having like a, you know, this, the winter hasn't been unusually dry or even average. So that's kind of a really, that's a message. I think that's resonating at least with the water resource community and people that rely on snow melt driven water supplies.

[00:37:35] Emile Elias: Thanks, connie. That was a great explanation. And it leads well into my next question, which is about the new normal and managing our landscape and the new normal. So we've talked a lot today about increasing temperatures and aridification occurring in parts of the Southwest. And that we might not be able to, we can't expect the same stream flow, for example, that as you just mentioned, despite the, a similar snowpack. Or we may not be able to expect similar rangeland conditions or agriculture surface water that we relied on in the past. So in your opinion, what's the best way to broaden our collective understanding of our changing conditions in the region. And do you have advice for people who are trying to manage in this new system. And we'll start with you, Connie.

[00:38:26] Connie Woodhouse: Yeah, I think getting back to my, my experience in the upper Colorado River basin well aridification is not a word that's maybe part of the conversation more broadly. The new reality of less water from now on has become an accepted reality, especially given the cuts that were dictated by Reclamation to the seven basin states to come up with ways to cut two to 4 million acre feet. That is huge. Since everyone is being pressed to find ways to cut water use permanently, and this is being considered permanent, maybe not for permanently, but definitely major cuts. This is engaging all sectors from agricultural to municipal to industrial uses.

[00:39:09] So to, to answer your question though while this has been front and center in the Colorado River basin, it's maybe not as obvious in other areas. And I think there's some clear lessons to be learned and to be shared from the Colorado River basin. And I also think we can learn a lot from people and communities who have lived through and still experience severe water shortages about how to live under increased aridity.

[00:39:31] And I'm thinking of particular tribal communities, but also internationally there's some good examples. So. You know, it's just a different way of thinking. And I think as we share these lessons as they're, you know, and unfortunately really hitting hard in some places, maybe that's the best way to broaden that collective understanding.

[00:39:49] Emile Elias: Mike, is there anything you'd like to add?

[00:39:51] Mike Crimmins: Yeah, I'll just say Connie brought up the snow pack example and I just think that such a good, it's such a stark clear example of what we're talking about here and it's, that will be evident in those wet years in the future. Right? I mean, we won't have to look very far to understand if things are working the way that they used to or they're not.

[00:40:10] And they probably won't. I think on the land management side, this just kind of came to me as Connie was talking there, there's kind of a, there's an old, and it's fairly vague term in climate called effective precipitation. And I'm wondering if we should resurrect the term like that and give it a little bit more clarity because it could be a way of engaging those that are really focused on, you know, precipitation to start having conversations around effective precipitation. And it can mean a lot of different things to different people, but it, I mean, in agriculture and in ag climate, it really means are you getting enough precipitation at the right time and the right amount to satisfy soil moisture requirements?

[00:40:51] Well, in an increasingly arid climate, increasing levels of PET, if we can come up with ways to sort of articulate that it did rain 12 inches, you know, last year, but effectively, you know, it yielded, you know, so many inches of actual soil moisture, and that has actually been changing over time. Maybe those are ways of sort of obliquely introducing these terms and into the conversations that are already kind of going on. Right. And I guess it, it does say things about like more effective, more widespread soil moisture monitoring, sort of the, you know, measuring directly what we're trying to, what we're worried about with a lot of these ecosystems and agro ecosystems. You know, that's, you know, we're managing or hoping to get soil moisture to grow things in a lot of the situations.

[00:41:38] And so, soil moisture's gonna be a mediation between surface climate forcings and increasing aridity and precipitation or irrigation. So those kinds of things. And I'm really interested to, to kind of talk more with the wildfire community too, to sort of see what kinds of new metrics or new ways of thinking that they're interested in as you know, aridity increases, just to make sure that there are no surprises as we creep forward here.

[00:42:06] Emile Elias: Thanks Mike. We like to end our episodes by asking our experts to share what gives them hope. And so Connie we'll go ahead and start with you on what gives you hope?

[00:42:18] Connie Woodhouse: What gives me hope is this collective will that I've been seeing coalescing. Coming from really disparate groups to work together and deal with our changing climate.

[00:42:28] And particularly with regard to water resources. And again, this for me has been in the upper Colorado River basin. I mean, water shortages from such an you know, an important basin. This is not a problem that can be solved easily, and it's taking compromise from everyone. In spite of some of the discussion about who might have already paid their dues on that.

[00:42:50] It's not a problem that can be solved easily, and it's gonna take everybody working together. And my sense is that people have realized this. Not that compromise is in any way easy, but I think we're seeing that everyone needs to have a seat at the table for these discussions. And I think, you know, maybe it came, maybe it takes a catastrophe, which is what we're looking at right now to do this, but I've actually seen more good ideas and more people talking together about this than has happened in the past.

[00:43:18] And I guess, you know, with catastrophe comes hope. For me anyway.

[00:43:24] Emile Elias: We were just talking about that yesterday. I like that answer. Mike, the same question to you, what gives you hope for the future?

[00:43:32] Mike Crimmins: I'm gonna build right on Connie's answer too. And it's, you know, the crisis creates the opportunity, right? And I think that the water situation and honestly, the crisis is causing people to, who maybe didn't wanna work together, work together.

[00:43:50] And it's showing that compromise is necessary. But I think that, that actually, I hope, and I think there's some evidence of that this is extending into the climate sphere too, is that, you know, okay, we work on water, but we need to work on climate more broadly. And if we can do water, we can do climate. Right.

[00:44:04] And we should think about them together here in the Southwest. And so, and it does give me hope that I think this will spur on more working together and having agriculture participate in the solutions to climate change rather than feeling threatened by, you know, policy and those kinds of things. So I'm hoping this is the advent of this new era of good, solid, compromise and working across the aisle and, you know, getting the job done on this stuff, cuz we can't continue to punt anymore. The water situation is clearly shows the punting can only go so far.

[00:44:37] Emile Elias: Excellent. I am very hopeful based on your responses to that question that we're moving forward from crisis to opportunity. And before we wrap up, I'd like to mention that Mike, you co-host a podcast of your own, the CLIMAS Southwest podcast.

[00:44:54] And do you wanna say a quick word or two about that in case our listeners are interested in checking it out?

[00:45:00] Mike Crimmins: Oh, thanks, Emile. It is probably not as informative as this podcast. But we have a lot of fun. And so we're kind of in the heart of the monsoon season. And so it's Zack Guido and Ben McMahan and I, basically whining about whether or not it rained in our backyards or not.

[00:45:18] And hopefully a little bit more information more broadly about how the Southwest climate works, but there is quite a bit of whining. Less so now that it actually has rained at my house, but you can find it at the Climate Assessment for the Southwest website.

[00:45:30] Emile Elias: Excellent. Thanks. And don't, you have some sort of competition that you do on your podcast as well, related to the monsoon?

[00:45:36] Mike Crimmins: We do, we have this thing that we're running it for the second year, a Southwest monsoon fantasy competition. And so it's actually too late to sign up at this point. But if you got in on the ground floor in June, basically what it is, you make a guess of what five cities across the Southwest are gonna get, as far as precipitation each month. And you're you gain points on that. So you can hedge and you can come up with pretty complicated assemblages of precipitation totals, or you can just guess like I did and you can win prizes. And it's been pretty fun. We've had 300 people last year, 500 this year.

[00:46:15] And it's been a very interesting monsoon so far, so we'll have to see how next month plays out as well.

[00:46:21] Sarah LeRoy: Mike, I'm curious how accurate your guesses were.

[00:46:25] Mike Crimmins: Oh, they've been terrible. So, so, and I always use the, I, you know, as a climatologist, I just stick with climatology. And as you know, well, I mean, on, over, on average, over time, it should work out really well.

[00:46:40] But in any given year it's pretty useless.

[00:46:44] Emile Elias: Okay, I'll be looking for that for next year. That's my kind of fantasy football. Thanks. And thanks to Connie Woodhouse and Mike Crimmins for joining us today; it's been great to talk with you.

[00:46:54] Mike Crimmins: That's great, thanks!

[00:47:00] Emile Elias: Thanks for listening to Come Rain or Shine, podcast of the USDA Southwest Climate Hub

[00:47:05] Sarah LeRoy: and the USGS Southwest CASC. If you liked this podcast, don't forget to rate or review it and subscribe for more great episodes. A special thanks to our production crew, Skye Aney and Reanna Burnett. If you want more information, have any questions for the speakers or would like to offer feedback, please reach out to us via our websites.